News

September 6, 2021

Science is based on promises, not on mere rules

© LAIMAN-ARIGA

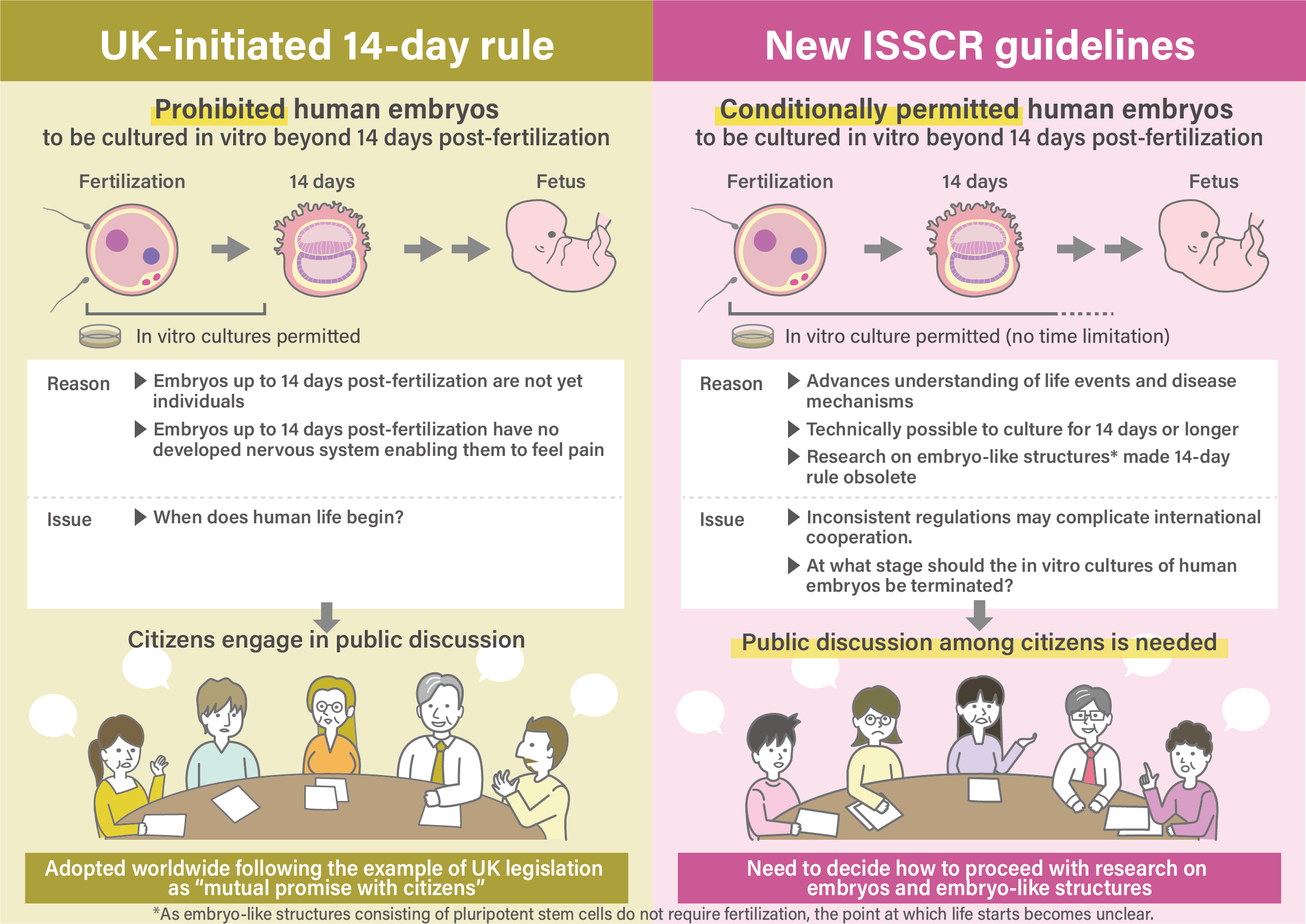

In embryo research, the “14-day rule” has been considered paramount in ethics research. Regardless of it being a law or guideline in their respective countries, all ethical scientists respect it as a de facto international regulation. However, earlier this year, when the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), the world’s largest society for academic research on stem cells, published its most updated guidelines, the 14-day rule was no longer included. In a new essay in EMBO reports, ASHBi Assistant Professor and bioethicist Tsutomu Sawai and his colleagues explain the implications of this removal.

Ethics are an important part of science. Research must be done in a way that prioritizes the interests of patients, respects the dignity of animals, and is consistent with the values of society. This is especially true for scientific research using human embryos, which can evoke particularly strong reactions from the public.

The 14-day rule was established nearly fifty years ago as a compromise between groups with different perspectives: those who emphasize the sanctity of life and those who see the need to advance scientific knowledge. While dystopic novels may only imagine worlds of eugenics, embryo research is critical for understanding natural causes of embryo destruction, such as miscarriages, and also life-threatening risks to the child or mother, such as preeclampsia.

The 14-day rule is not international law, although some nations, such as Britain and Japan have adopted it, as a law or guideline. Furthermore, regardless, wherever scientists work, they are expected to respect the 14-day rule, because it is seen as a de-facto international rule by the international scientific community, who will chastise research that is considered unethical, and the ISSCR’s guidelines have played an important part in it.

The decision to remove the 14-day rule, the authors caution, may mislead scientists and policy makers into thinking that it is no longer relevant. To make this point, the essay reminds readers that bioethics is based on a balance of political judgement, or promise, “to respect moral views whether it be the sanctity of life and to advance research in a responsible way.”

Following such promises, the authors claim that countries should not automatically amend their laws on embryo research.

“Each country will need to make thoughtful decisions reflecting on past promises,” said Sawai and his colleagues.

The article expresses concern that the ISSCR may not have given the consequence of the dissolution of the 14-day rule enough consideration, since its new guidelines did not draw any alternative limit on embryo research, such as the appearance of nerve cells.

Countries including “Japan should not and need not follow the ISSCR’s guidelines thoughtlessly and without adequate discussions,” they stressed.

These discussions should include not only stakeholders but also citizens of each country before a decision about upholding the restriction, relaxing it, or even tightening it.

If decisions are made without sufficient discussions, the authors warn that the public may perceive the ISSCR as having unilaterally broken its promise, which risks the public’s trust toward future scientific research.

Another concern is that the international cooperation on embryo research may be compromised, since some nations may continue to respect the 14-day rule while others do not. That is why the essay also proposes an international registry for embryo research is made. Similar registries already exist for human heritable genome editing.

However societies respond to the ISSCR’s decision, Sawai says the essay was written to stimulate “more open public discussion on human embryo research.”

Paper Information

Tsutomu Sawai, Go Okui, Kyoko Akatsuka, Tomohiro Minakawa, “Promises and rules – The implications of rethinking the 14-day rule for research on human embryos” (2021), EMBO Reports, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202153726