Why It Is So Hard to Get Started on an Unpleasant Task

–Scientists Identify a “Motivation Brake”

We’ve all been there…

You know you need to make that complaint phone call, but you cannot bring yourself to dial. Or there is a project your demanding boss assigned, and even though you know you should start, you just…can’t. You’re stuck at the starting line, caught in that all-too-familiar sense of motivational paralysis.

Why is it so hard to just get started?

Now, scientists at Kyoto University’s Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Biology (WPI-ASHBi) have discovered what’s happening in the brain during these frustrating moments. The research team conducted research on macaque monkeys and identified a specific brain circuit that acts like a “motivation brake”: a neural pathway connecting two brain regions (the ventral striatum and ventral pallidum) that kicks in when we are confronted with tasks that come with negative consequences. When the scientists temporarily disabled this circuit, the motivational brake released: tasks that were once avoided suddenly became approachable. This discovery may help explain why, for some people (such as those living with depression), starting even simple tasks can feel impossibly hard. By identifying the brain “switch” behind this motivational paralysis, researchers may be one step closer to developing new treatments that help people overcome this invisible barrier.

The research is led by Dr. Ken-ichi Amemori, Dr. Jungmin Oh, and Dr. Satoko Amemori, with Dr. Masahiko Takada (Professor, Center for Human Behavior Evolution Research; currently Professor Emeritus), Dr. Ken-ichi Inoue (Assistant Professor; currently Associate Professor at Nagoya City University), and Dr. Kei Kimura (Assistant Professor, Tohoku University). The findings will be published in Current Biology on January 10th 2026.

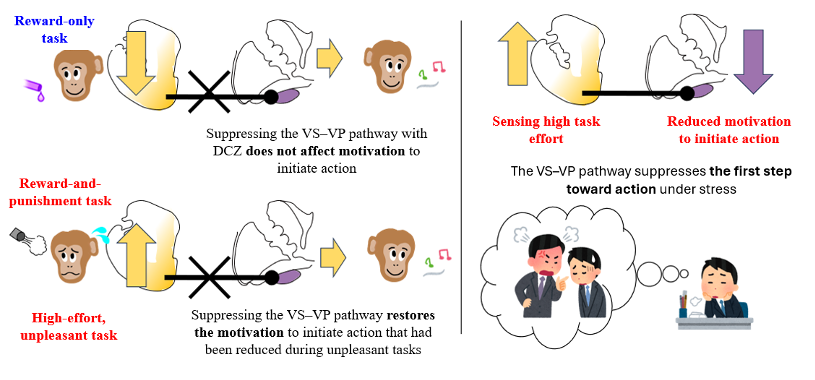

Monkeys were trained to perform two types of tasks: one that offered a reward only, and another unpleasant task that combined reward with punishment. The VS–VP pathway was temporarily suppressed using chemogenetics. In the reward-only task, motivation to initiate action was unchanged. In contrast, in the unpleasant task, motivation to start that had been reduced under stress was restored. These results show that the VS–VP pathway functions as a brake that prevents taking the first step toward action.

Background

Most of us know the feeling: maybe it is making a difficult phone call, starting a report you fear will be criticized, or preparing a presentation that’s stressful just to think about. You understand what needs to be done, yet taking that very first step feels surprisingly hard. When this difficulty becomes severe, it is known medically as avolition. People with avolition are not lazy or unaware: they know what they need to do, but their brain seems unable to push the “go” button. Avolition is commonly seen in conditions such as depression, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease, and it seriously disrupts a person’s ability to manage daily life and maintain social functions.

Research in neuroscience and psychology has suggested that before we act, the brain weighs how much effort a task may cost. If the cost feels too high, motivation drops. But until now, it has been unclear how the brain turns this judgment into a decision not to act. To explore this question, a research team at WPI-ASHBi applied an advanced genetic technique called chemogenetics to highly intelligent macaque monkeys, allowing them to adjust communication temporarily and precisely between specific brain regions and identify a circuit that acts like a brake on motivation.

Methods and key findings

The monkeys were trained to perform two types of tasks. In one, completing the task earned a water reward. In the other, the reward came with an added downside: an unpleasant air puff to the face. Before each trial, the monkeys saw a cue and could freely decide whether to start or not. The researchers focused not on which option the monkeys chose, but on something more fundamental: did they take the first step at all? As expected, when the task involved only a reward, the monkeys usually got started without hesitation. But when the task involved an unpleasant air puff, they often held back, even though a reward was still available.

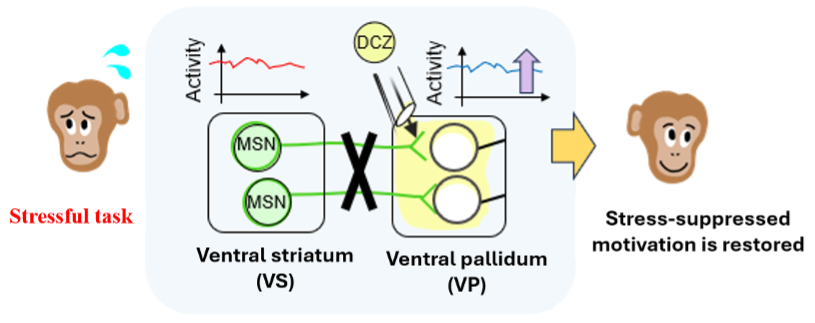

The researchers then temporarily weakened a specific brain connection linking two regions involved in motivation: the ventral striatum (VS) and the ventral pallidum (VP). In the reward-only task, suppressing this pathway had little effect on monkey behavior, and the monkeys initiated the task normally. In contrast, in tasks involving an unpleasant air puff, the mental brake to starting had eased: the monkeys became much more willing to start. Importantly, the monkeys’ ability to judge rewards and punishments did not change. What changed was the step between knowing and doing.

The researchers took a closer look at what was actually happening in these brain regions during this process. Neural activity in the VS increased during the stressful task, suggesting it helps the brain register when a situation feels stressful. In contrast, activity in the VP gradually fell as the monkeys became less willing to start the task, showing that these two regions play different roles. Together, these findings show that the VS to VP pathway functions as a “motivation brake” that suppresses the internal “go” button, particularly when facing stressful or unpleasant tasks.

Future perspectives

This discovery of the VS–VP “motivation brake” may shed light on conditions such as depression and schizophrenia, where severe loss of motivation is common. In the future, interventions such as deep brain stimulation, non-invasive brain stimulation, or new drug strategies might aim to fine-tune this brake when it becomes too tight. But this “brake” exists for a reason. While an overly tight brake can lead to avolition, a brake that is too loose could make it harder to stop, even in excessively stressful situations, potentially leading to burnout. In other words, the VS–VP circuit may help keep motivation within a healthy range. “Over weakening the motivation brake could lead to dangerous behavior or excessive risk-taking,” said Ken-ichi Amemori, lead author of the study. “Careful validation and ethical discussion will be necessary to determine how and when such interventions should be used.”

In modern society, especially at a time when burnout is at an all-time high, these findings invite us to rethink what “motivation” really means. The brain can actively dampen the drive to act when tasks are unpleasant or stressful, so getting started is not simply about willpower. Rather than trying to forcibly boost motivation, the focus should shift toward how society can better support people in coping with stress. This is a question that warrants broader societal dialogue.

Researchers introduced artificial “switches” into specific brain cells in the ventral striatum. By giving a drug (DCZ) to a connected brain region, the ventral pallidum, they were able to temporarily weaken communication along this pathway, allowing them to test its role in motivation.

KYOTO, Japan – Jan 2026

Glossary

- Chemogenetics: A method for remotely controlling selected brain cells. Researchers first give specific neurons an artificial “switch” (a receptor) using a gene-delivery tool. They can then turn those neurons up or down for a short time by giving a drug that only works on that switch, letting them test the role of a particular circuit.

- Ventral striatum (VS): A brain region involved in reward, motivation, and learning. Part of it is also called the nucleus accumbens.

- Ventral pallidum (VP): A brain region that receives signals from the ventral striatum and helps pass them on to other parts of the brain. It is an important hub for turning motivation-related signals into action by relaying and combining information sent to areas such as the thalamus, midbrain, limbic system, and prefrontal cortex.

Written by Heyuan Sun (EurekAlert!)

Paper Information

Oh, J. N., Amemori, S., Inoue, K., Kimura, K., Takada, M., & Amemori, K. (2026). Motivation under aversive conditions is regulated by a striatopallidal pathway in primates. Current Biology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.12.035

Related links

Can’t get motivated? This brain circuit might explain why — and it can be turned off (Nature News)

Why Your Brain Puts Off Doing Unpleasant Tasks (Scientific American)