Teenage hormonal shift surprises scientists – opposite impacts on kidney injury

New research has shown that puberty plays a key role in shaping kidney health in adolescent girls, revealing a surprising shift in how the kidneys respond to injury. Although estrogen is known to protect against kidney damage in adult women, a recent study has found that the hormonal surge during puberty may instead increase the risk of kidney injury in adolescent girls, raising important questions about how sex hormones influence kidney health throughout life.

Kidney disease is a significant health concern, with previous studies suggesting that estrogen has a protective effect. However, clinical observations and animal research have suggested different effects during puberty, where kidney function appears to deteriorate in some individuals. Researchers in Japan have now confirmed that the period of rapid growth and hormonal changes during adolescence can make the kidneys more vulnerable to ischemic injury, which occurs when the kidneys are deprived of oxygen.

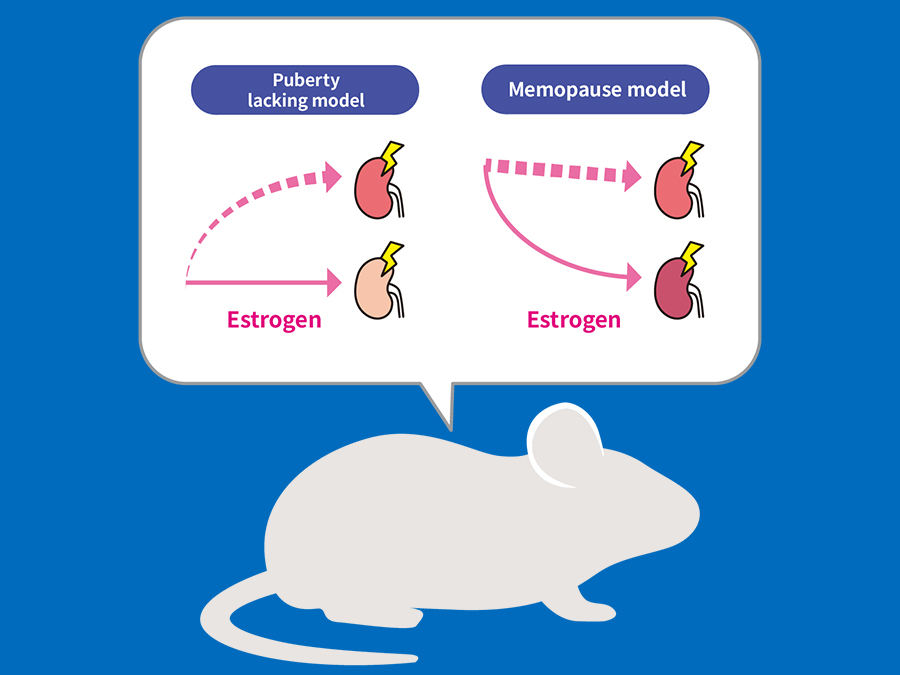

The researchers explored this issue using a mouse model to assess the impact of female sex hormones before and after puberty and during adulthood. They removed the ovaries to halt hormone production in mice at different life stages, and then induced an ischemic injury to measure the response of the kidneys. Surprisingly, they found that mice whose hormone production was stopped before puberty were better protected against kidney damage than mice that experienced a rapid increase in sex hormone production like in puberty. However, mice whose hormone production was stopped in adulthood—like in menopause—were more vulnerable to kidney damage than mice whose sex hormone production stayed normal.

“Puberty is a time of significant tissue growth and change,” explained Dr. Kitai, lead researcher of the study. “Our study shows that female sex hormones can increase susceptibility to kidney injury during this time, which contrasts with the protective effects of these hormones in adulthood.”

One of the study’s key discoveries is centered on a protein known as insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), which is important for tissue growth. The researchers found that IGF-1R levels in the kidney decreased during and after puberty, while the levels stayed higher in the kidneys of mice whose hormone production was stopped before puberty. Mice with lacking Igf-1r (the gene responsible for producing IGF-1R) in their proximal tubules (an active region of the kidney) during postnatal kidney growth showed increased susceptibility to ischemic injury. These findings suggest that strong involvement of IGF-1R signaling during postnatal growth helps protect the kidneys against ischemic injury in mice that were not exposed to the hormonal surge in puberty.

These findings provide important new insights into how puberty influences kidney health. The study suggests that the developmental changes driven by the hormonal surge in puberty may override the protective benefits that female sex hormones offer later in life. This could help explain why some individuals with chronic kidney disease experience a decline in kidney function as they enter adolescence, a trend that has been observed in the clinical setting but has not yet been fully understood.

The implications of this research extend beyond basic science, as understanding how sex hormones regulate kidney injury susceptibility could lead to improved treatments for kidney disease. “Pubertal female sex hormones may play a critical role in how kidney disease progresses during adolescence,” said Dr. Kitai. “This study highlights the need for further research into the long-term impact of puberty on kidney health.”

In the future, the researchers plan to further explore the mechanisms behind these findings and investigate potential interventions to mitigate the increased risk of kidney injury associated with puberty. By uncovering how hormonal changes affect the kidneys during this crucial developmental period, they hope to contribute to strategies that improve kidney health outcomes for women and girls in different life stages.

Writing: ThinkSCIENCE, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan)

Paper Information

Kitai, Y., Toriu, N., Yoshikawa, T., Sahara, Y., Kinjo, S., Shimizu, Y., Sato, Y., Oguchi, A., Yamada, R., Kondo, M., Uchino, E., Taniguchi, K., Arai, H., Sasako, T., Haga, H., Fukuma, S., Kubota, N., Kadowaki, T., Takasato, M., … Yanagita, M. (2024). Female Sex Hormones Inversely Regulate Acute Kidney Disease Susceptibility throughout Life. Kidney International. 10.1016/j.kint.2024.08.034.